Sailing Adventure Aboard AraVilla (No Motorcycles Involved)

'Wednesday November 3rd, 2021 7:30'

This adventure is over.

"She left you with many gifts." Duncan said of Brooklyn. Those words continue to regularly echo in my consciousness, especially on this trip. As I move forward through this life diverted, the meaning of those gifts continues to make itself apparent. "If not for her, I would not be here." I would often think as I sat in the dark on yet another watch alone with my thoughts as angry waves bashed the hulls of this beautiful boat.

If not for her I would not be the person I have slowly been becoming.

There was still an open question as to whether we would follow a path down the coast and the along the islands or whether we would do the run out to just South of Bermuda and then due South to Saint Martin. It would all depend on the weather report. "I hold onto my goals loosely." I mentioned to Dana.

Dana uses paper charts, pencils, and erasers to plan his routes.

Because our departure was significantly delayed due to the blown out sail, we missed our original weather window. "We have to do what makes sense for safety." Dana explained.

We had spent a down day waiting for this weather system to move through. The weather service Dana employs predicted the rains would stop around 9AM the next morning. With uncanny accuracy, the rains stopped exactly when predicted. We raised anchor and headed to the gas dock to fill the diesel and water tanks. It would be the last time for over a week that we would touch land.

Earlier, I had heard from my friend Milner who lives near Norfolk. He wanted to try to snap a few photos of the boat as it went by. He's become quite the accomplished photographer. I mentioned it to Dana and he agreed to sail closely by Fort Monroe where Milner would be waiting. It was only slightly out of our way. Dana raised the mainsail and we sailed past the fort where Milner captured some nice images of the AraVilla.

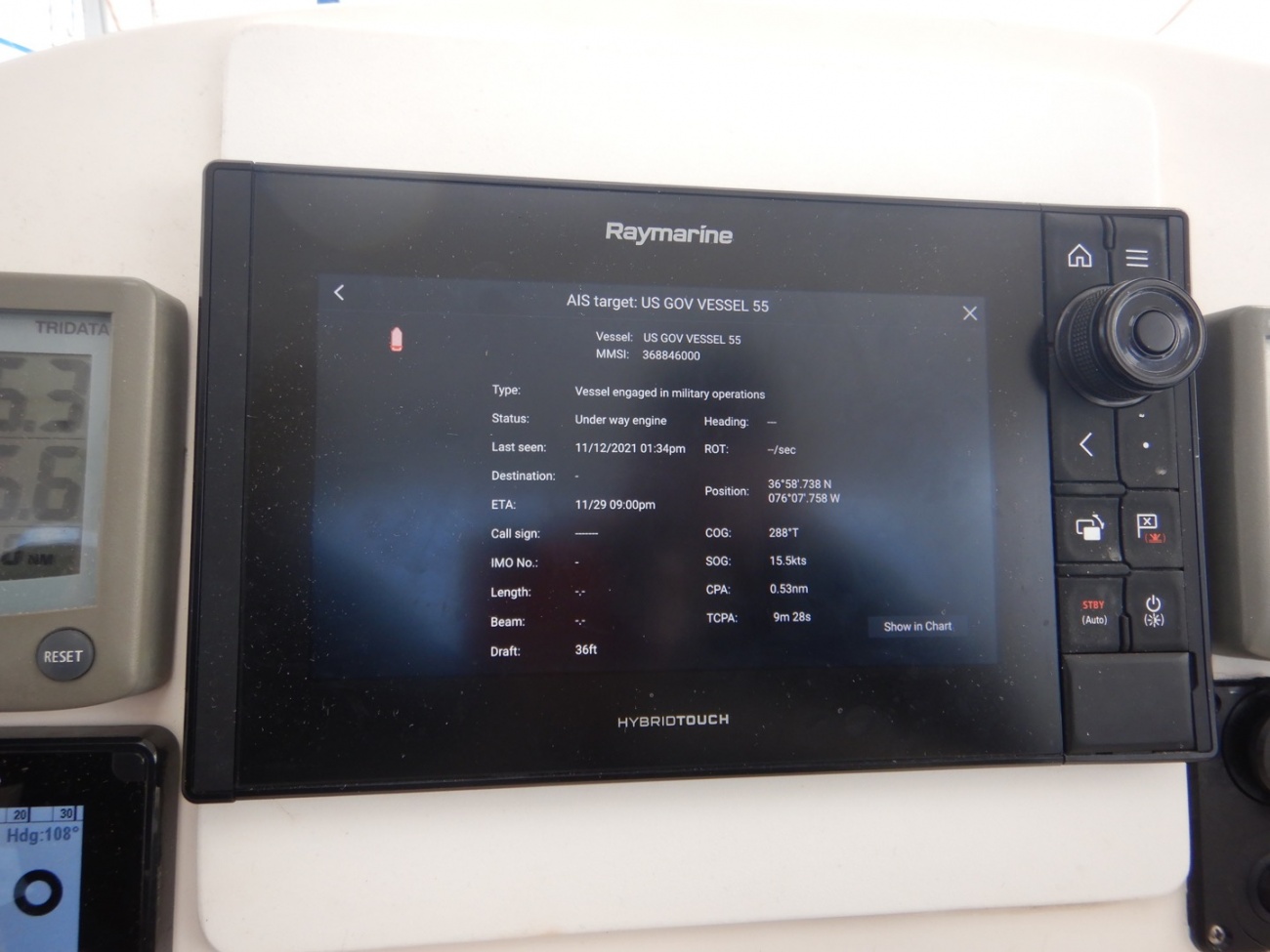

Not long after, we approached the Southern Chesapeake Bay Tunnel and Bridge system where we encountered a destroyer.

The catamaran is equipped with an Automatic Identification System (AIS) capable chart plotter. We could see the destroyer on the chart plotter and then simply by clicking on it we could see quite a bit of information about it.

I pondered how in ages gone by getting this amount of detail about a vessel was nearly impossible and would often involve spies.

We crossed the Bridge and Tunnel system and as we approached the Atlantic Ocean we turned roughly South towards Cape Hatteras. We skirted the coast so we'd have signal for a bit longer.

As is well known, I don't sail. Neither does the other crew member, Peter. As a result I wanted to learn as much as I possibly could as quickly as I could. My thinking was that the more I could learn the more load I could take off Dana. I probably overdid it peppering him with an endless array of questions about emergency procedures, sailing technique, sail trim, and every other topic I could possibly think of. I didn't realize it at the time, but I think causing him to think through the things he does knocked him out of his rhythm. Mistakes were made. "For me it's all just muscle memory. I'm not a teacher. This is something I know about myself." he explained. Nevertheless, he patiently answered every question I threw at him.

I spent much of that first day at the helm.

The Watches

Once we left Norfolk, we started running a 24hour a day schedule. The boat would not stop until we reached Saint Martin. By the time we had made the turn towards Cape Hatteras it was pretty clear that we would turn out to sea at a course of 135 to a point roughly 200 miles South of Bermuda. "There'll be a few bumpy days, but nothing too bad." Dana said ominously.

During day time hours we would switch off duty at the helm as we felt like it. However, overnight, we were more formal about the schedule. We divided the overnight hours into three hour watches. Peter was on watch from 9PM to 12AM. Mine was from 12AM to 3AM. Dana took the 3 to 6 shift at which point Peter was up again.

Peter and I had suggested that we drop the sails overnight and just use the engines because then we could more easily handle course corrections and other problems without having to wake Dana up. At that point, neither Peter nor I felt confident adjusting the sails. "This is a sailing vessel! We're going to sail her!" Dana declared. It's his boat and he's the captain. "Aye, aye, Sir." and that was that.

I was however quite concerned as both Peter and Dana were not sleeping well at all and the fatigue was starting to take its toll.

My friend Phil, who is a professional sailor among many other things, had debriefed me on "watch etiquette". He had nearly hit a shipping container at one point and hit home the concept of scanning the chart plotter, the radar, and then the horizon. Dana had a friend who recently lost a boat out at sea presumably due to hitting a container. Fortunately he was rescued. "Containers are probably the number 1 hazard to pleasure craft out here." Dana said.

That got my attention.

That first watch as we were skirting along the coast was the first time I had been on ocean at the wheel of a vessel at night. Try as I might, I could see nothing. It was pitch black except for some lights that could be seen on shore and the lights of the few boats in the distance. This would be true for each of my watches. I was reduced to just paying attention to the AIS and the radar. I would still dutifully scan the horizon just in case maybe something might reflect some moonlight, but it was futile.

One thing that surprised me was that with very few exceptions the boat was kept on course by computer. The AraVilla is equipped with a gadget called an Auto-helm which allows you to set a compass direction and then it does its best to keep you on that course, unless it loses its ever loving mind. Making course adjustments amounts to just pressing a button. So in general there is very little to do on these watches.

Despite this, the watches were challenging and exhausting. There's nothing to see. There's nothing to do with the exception of occasionally adjusting the auto-helm. "This hour I got to push a button. That's 100% more than I did last hour."

However, things got interesting when the wind direction or speed changed. Every evening before he went down, Dana would say, "The sails are set. The wind is predicted to stay at this angle until morning so there'll be nothing to do."

And you can hear Morgan Freeman saying, "But the winds did not stay at this angle."

And every night on my watch, the winds would change.

Catamarans have this issue that I did not realize. They don't do well when the wind is coming roughly from the front. The closer the angle of the wind is to the front, or bow, of the boat, the "closer to the wind" one is sailing. How close one is is measured in degrees off the bow, either to port (left as one sits at the helm) or starboard (right). If the wind is coming from directly in front of the boat, the angle is 0. If the wind is coming directly from the side it's 90. If it's coming from behind, it's 180. The side the sails are put and what position they are put into depends on the side and angle of the wind. The problem is that on a catamaran if the wind is coming from anything less than 60 degrees the boat loses forward motion. Monohull boats can apparently sail much closer to 45 degrees or so.

So there I sat, the sails set often for winds coming from 60 degrees when it would change. If it changed to be more from the side it wasn't a problem. The sails wouldn't be ideally set for that wind position but it wasn't something I'd need to wake Dana up for. However, if the wind changed so that it was coming from some position less than 60 degrees, I'd have to adjust course based on what the wind was doing to try to keep the wind coming from something 60 degrees or higher. I couldn't lower the sails by myself and I really didn't want to wake Dana up since he was at such a sleep deficit.

So there I would sit occasionally pressing a button as the winds changed direction. It meant we weren't exactly on course but at least I didn't have to wake him up. If I didn't do it with the right timing the sails would flap loudly. It's very disconcerting when that happens and I worried it would wake him up.

Another issue that one had to pay attention to was if the wind speed increased. A monohull sailboat will tilt, or heel, as the force of the wind increases so one gets some feedback as to what the boat is doing. If the wind gets too strong it'll just heel over pretty far but it won't flip. Not so with a catamaran. If one has too much sail up for a given wind speed especially when combined with waves coming from the side, there is a real risk of tipping a catamaran over.

Every catamaran has this chart called a "Wind Chart" where the manufacturer specifies how the sails should be pulled in at what wind speeds. The front sail is rolled with a line that runs to the helm. There are red lines on the sail to show how far it's been rolled in. The main sail, however, can only be raised or lowered from the mast so someone has to walk on deck to adjust it. This boat has three "reef points" in the main sail. You can either have it all the way up, or pulled down to two other points. According to the manual, for example, if the winds are over 20 knots they recommend pulling the main down to the first reef point and pulling the headsail in a bit (if memory serves). Sadly, it happened a few times that winds picked up dramatically, and along with that the waves, at which point I'd have to wake Dana up and he'd go forward to lower the sail down a bit and make other adjustments while the boat pitched violently up and down in growing waves as if we were in one of those deep ocean adventure films, you know, at that point right before everything goes horribly wrong, waves crashing over the side.

We got into the habit of "reefing" the sails ahead of time before Dana went down so there would be less likelihood of having to wake him up. Again, lack of sleep was really taking its toll on both of them.

Pan. Pan.

"Eat up boys. This is the last hot meal you'll get for a few days. It's going to be bumpy."

It was something like the second or third watch, when we ran into the start of "weather". The wind had picked up to a steady 23 knots with waves larger than I had previously encountered. Our best guess was that they ranged from 6 to 12 feet or so. It was explained to me that these were not big waves. It's a 46 foot long boat after all. Both Peter and Dana were below exhausted and trying their best to sleep . The sail was up but at its lowest reef point and the head sail was pulled all the way in. We were running one engine doing about 5 knots. I had read in multiple sources that when winds and waves combine that one should turn "into" the wind to try to lessen the bumpiness a bit and decrease the force on the sails. Waves were crashing over the bow and I was trying my best to keep the wind at 60 degrees as I had read I was supposed to.

I didn't want to wake Dana up. I had been in rough weather before on my power boat, back in the day, and I thought 5 knots was pretty slow. But nevertheless waves would relentlessly come. The boat would climb and then slide down the other side sometimes crashing down loudly burying the bow into the water. These were not big waves so I was not afraid of tipping or anything of that seriousness but it was nevertheless uncomfortable. But I certainly did not want to take these waves from the side. So I kept this course as the wind howled and the waves crashed.

Then there was a particularly large wave. The boat pointed dramatically up and the wave broke beneath the boat and I heard a loud crash from the salon that I feared I recognized.

Our new coffee maker carafe had shattered.

PAN. PAN.

We have lost the coffee maker.

I repeat, we have lost the coffee maker.

Cue the Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.

Shit had just gotten real.

Dana chided me for running the boat too quickly over the waves so I pulled the engine back so we were running about 3 knots. That made the ride a bit more comfortable but it was still quite bouncy. That night we got hit by a few squalls while I was at the helm. The lightning show all around us was impressive. Dana has a pressure cooker on board and if there is a risk of a lightning strike it acts as a kind of faraday cage for small electronics, so we put his handheld gps and radio in addition to my Garmin InReach into the pot and secured the lid. The thinking is if all the electronics on the boat are toast we would still be able to navigate.

The waves and wind would not let up for another three days. For some reason, I cannot explain, despite having a forward cabin and getting bounced around dramatically, I was for the first time in well over a decade able to sleep soundly through the night, well after my shift, for a solid 7 hours without waking up once. When I mentioned this both Peter and Dana looked at me like I was nuts.

Deadliest Coffee Maker

Losing the coffee maker was a tragedy. "Without coffee there is no life." I declared. So as we were pitching and bouncing around in these waves, this way and that, I performed a potentially deadly balancing act using a tea kettle to boil water and then pour it through a filter directly into a cup. Dana and Peter were skeptical but I was, in fact, able to make coffee for all takers consistently despite all the turbulence without dropping this delicately balanced assembly even once. I performed this service daily.

The Strangely Meditative Nature of Kansas

Within a few hours of having turned away from Cape Hatteras roughly towards Bermuda the nature of the water changed. It was not long before we could no longer see land and in every direction it looked the same. Soon there were no boats to see. There were no birds. At one point we did see a pod of porpoises on that first day out at sea, but after that we would not see any creatures of any kind, with the exception of two mahi Dana caught, until a seagull near Saint Martin. I had expected to see some signs of life Out There, but there were none.

After the second day it dawned on me that there were no insects. There were no fish jumping. There was nothing. It was just this now Very Little Boat alone out in a very big ocean. There were only four colors to see. Sea Blue. Sky Blue. White. Grey.

I closed my eyes and counted the colors I saw. One.

Opening my eyes, I realized that this scenery around us, despite its beauty, was really only about 4 times as interesting as the inside of my eyelids.

I had this feeling that I had seen a place like this before. It quickly became clear that there are many parallels between long distance motorcycle trips and sailing trips. For this parallel, when you travel across the US from interesting East to interested West you have to journey across a great flat place consisting also of only 4 colors.

"This is basically Kansas." I declared to the void. The void, however, was to particularly interested in my epiphany.

The days quickly fell into a strange rhythm. Sitting in one spot for three hours became easier, even in the chop. The days went by quickly. I was either up at the helm staring out into the quiet emptiness which was particularly oppressive on the night watches. Or I was down doing dishes. I tried to work but that didn't work out so well with the boat being bounced around like it was.

There was no service. I did have my Garmin InReach satellite messenger which I started to use sporadically to let people know we were ok. But without relentless stimulation of endless interruptions from a smart phone gadget or things to do, I found my mind quieting. There was less noise. Life became very simple. On watch, sit. Scan the AIS and radar. Look out at the moonlit ocean. Ponder. After watch, go to bed immediately. This was Dana's rule. I would go to bed and no matter how rough the seas were, I fell asleep instantly. Sleep almost exactly 7 hours. Get up. Make the worlds deadliest coffee. Alternate between sitting at the helm, sitting in the salon, or sitting in the cockpit area. I was unable to sleep during the day so that was not an option. Do dishes.

Repeat.

On that second night I looked up through the helm hatch and noticed the constellation of Orion clearly overhead, more clearly than I have seen it since I was a kid. The moon was waxing so each night lit up more and more of the ocean. Try as I might I could not get a decent photo. I would note that towards the end of my watch the moon would set over the horizon. Each night I would stare at it. There is something to a moon rise and set on the ocean. I've never seen anything like it.

I started to become aware of patterns in the way the water behaved when the wind changed. I started to notice all kinds of details that would normally be invisible to me. I delved into the screens on the chart plotter and in short order had the thing figured out completely.

I could focus. Clearly focus.

I looked at the adventure camera I've owned for the last 4 or so years and realized there were entire sets of menus and features on the gadget I had failed to find.

For the first time, I think, I got a glimpse into life before technology, despite being surrounded by it. Lacking a constant in influx of new information and stimulation, the mind quiets and becomes more present. The lack of stimulation prompts the mind to find some in smaller details. Things become clearer. Life becomes much more narrow but with that narrowness comes a depth.

I would ponder work. There's a great guilt I feel for not working. By the time I get home I will have been away almost a month.

I must be Doing. I must work. I know that what I have built is not yet nearly good enough and needs a tremendous number of hours of polish work. There are huge efforts that remain as I transition this platform away from all this legacy code I've written to the new stuff which will enable me to make it all much prettier and more functional. I've been dreading some of that for months now. I've pondered and pondered how to lessen the work I need to do.

Out Here however, having not worked and just sat for so long, suddenly an answer became very clear for how I can solve one of the bigger technical hurdles I face. In retrospect, it was obvious but with all the noise in my head I couldn't see it.

(As I wrote this sitting here at the Yacht Club, I was suddenly interrupted by a stunningly beautiful young woman who caught the glass of water my notebook was leaning up against before it fell over. She saved my notebook. I got pulled into a conversation with her and her mom about a variety of topics including this platform. The young woman, Samantha, really liked the concept and upon seeing a few screens was able to articulate clearly and concisely some features I could add to make it much more effective at engaging a younger audience. "Here's an 18 year old perspective." she said. Invaluable. If the nursing thing doesn't work out, she's got a future in user experience design.)

Dana had to cut a line at one point and I asked him for the smaller end. I taped it off and decided to try to learn how to tie a bowline. Peter had tried a number of times. Sometimes he got it. Sometimes he didn't. Frustrated, he would just toss the rope.

Having nothing to do, nothing to look at, no where to go, and having exhausted all the gadgets I could crawl through I focused on the bowline. I'm told it's the most useful knot on a sailboat. Dana had showed me how to tie one but I didn't get it. Critically, I thought, "When I was 18 someone could show me something once and I'd remember it." Mental decline, clearly.

I looked it up in a book. And then I just sat during a watch with my little rope and mis-tied the knot repeatedly, carefully analyzing each mistake I had made. When I happened to accidentally tie the thing correctly I would carefully analyze the knot to see if I could understand how the forces worked. There was nothing else to do so I didn't care that it was taking me an embarrassingly long time to figure out what I was doing wrong.

And then suddenly, I got it. I could tie the stupid thing without looking. The next day I did the same thing repeatedly until it was muscle memory. It's a stupid simple knot. Maybe it's not mental decline but instead just a mind filled with too many things to focus effectively.

I've have long known that I do better when I am Away on one of my long motorcycle trips. Strangely, this sailing trip has had the same kind of effect. I seem to do better in motion. I once again ask myself the question as to whether or not I can hold on this state of being when I'm back at "home". I know what's coming. As soon as I step back into the house, the crush of obligations will weigh me down again and I'll grind to a halt until the next time I venture away.

The Ocean

When the ocean is not angry it is stunningly beautiful. There is a blue out here that photos do not capture. As a matter of fact, there's next to nothing that photos really capture about this voyage and yet I still try.

Sunsets

The sunsets were simply not to be believed. The moon rises and moonsets were similarly stunning but I was unable to capture any good photos. Dana, however, was. I'll have to get some photos from him.

Destination

There were so many thoughts, insights, conversations, happenings, and other details that have since slipped into the void.

After 8 days at sea sailing 24 hours a day covering 1629 miles since leaving Norfolk, we arrived at Saint Martin in the early morning.

The last two days were nice sailing on relatively calm waters. The bouncy days were challenging. The last watches were the hardest. The crossing was calming but also very challenging. I cannot say that it was "fun". It wasn't. It was work. Real work. There were moments of minor terror.

But there is something to this sailing thing and if asked to do another crossing on this vessel I will jump at the chance.

The intervening many days since we've arrived here have involved a lot of boat work. Dana has been going almost non-stop since we tied up to the mooring. "Energizer Bunny" There's been an incredible amount of work accomplished. I had several days where I was strangely lethargic and had little energy to do much but I tried to help where I could. There are still a couple of days left before I return. Connectivity here, especially out on the water, is iffy at best. Today was the first chance I've had to do any writing, but it's been too many days since the crossing and so many details fall through the crack.

Before this trip, I never imagined I'd be able to do something like this. Every single person I've met here who has asked me how I got here, when I told them I was just an inexperienced crew member, looked at me in disbelief. It just doesn't happen. There are many stories to tell. It's a different world down in Saint Martin.

I hope to come back.

You must be a member of this group to post comments.

Please see the top of the page to join.